Why Revenue Forecasts Fail: The Complete Guide to Pipeline Erosion and Forecast Accuracy for B2B Sales Leaders

It's the first week of Q3. The forecast call shows $4.8 million in pipeline for the quarter, with $3.2 million in commit. Leadership likes what they see.

By week six, two deals have slipped their close dates to 'end of quarter'—still technically in the number, but now back-loaded. One $280K opportunity went dark after the champion changed roles. The commit holds at $2.9 million, but the deals underneath it have quietly reshuffled.

With two weeks left, procurement enters the picture on your largest deal and opens a competitive RFP. Another deal, verbally committed for months, reveals that legal review hasn't actually started. A third compresses from $380K to $260K to 'get it done before quarter-end.' The forecast drops to $2.4 million, and the team scrambles to find pipeline that can close in fourteen days.

On the final day of the quarter, the number lands at $2.1 million. Leadership wants to know what happened. But the honest answer is that nothing happened suddenly—the erosion was visible in week six, predictable by week ten, and inevitable by week twelve. The organization just wasn't structured to see it.

This scene plays out in revenue organizations every quarter, and most teams treat it as bad luck—a few deals broke the wrong way, a competitor swooped in, a budget got frozen. But here's the uncomfortable truth: that erosion was visible weeks before the quarter ended. The signals were in the data. The problem is that most organizations aren't structured to see them, and the ones that can see them often lack the operating discipline to act.

Pipeline erosion, compression, and stalls are not random. They are structural, measurable features of complex B2B sales systems. Academic research on CRM analytics and Harvard Business Review's extensive work on forecasting bias converge on the same conclusion: organizations systematically overestimate future revenue because they underestimate variance and ignore early warning signals. For CROs and RevOps leaders willing to look honestly at their data, the opportunity is to reframe the pipeline as a probabilistic portfolio, manage forecasters as rigorously as deals, and design an operating model that treats erosion as a controllable variable rather than a quarterly surprise.

The Language of Erosion

Before we can fix the problem, we need precise definitions.

a Sales Pipeline is a portfolio of opportunities, each with an evolving probability of conversion and an associated revenue value. The expected value of that portfolio at any moment equals the sum of each deal's value multiplied by its true probability of closing. The challenge is that 'true probability' is unknowable—we only have estimates, and those estimates are systematically wrong.

A Forecast is a prediction of revenue that will close within a defined time period, typically a quarter. It is a filtered view of the pipeline, including only those opportunities expected to close before the cutoff, weighted by some combination of stage, rep judgment, and historical pattern. The forecast inherits all the uncertainty of the underlying pipeline, then compounds it with timing risk: not just will this deal close, but when.

A pipeline can be healthy while a forecast is broken, if the deals are real but the timing assumptions are wrong.

A simple way to think about it: pipeline answers 'what's possible,' forecast answers 'what's probable within this window.' The table below summarizes the key differences.

| Dimension | Pipeline | Forecast |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The full portfolio of open opportunities, regardless of when they might close | A time-bound prediction of what will actually close within a specific period |

| Time horizon | Open-ended; includes deals that might close in 6 months or 18 months | Fixed window, typically the current quarter or month |

| Primary question | "What could we win?" | "What will we win, and when?" |

| Risk profile | Stage risk (will it progress?) and qualification risk (is it real?) | Adds timing risk (will it close in time?) and compression risk (at what value?) |

| Typical categories | Early stage, mid stage, late stage | Commit, best case, upside |

| Example | A $500K opportunity in Discovery with a Q3 close date sits in pipeline but not in Q1 forecast | The same deal, now in Negotiation with a signed LOI and March 15 close, enters Q1 commit |

| How it fails | Overstated when qualification is weak or stages are inflated | Overstated when timing is optimistic or rep confidence exceeds historical accuracy |

| Primary metric | Coverage ratio (pipeline ÷ target) | Forecast accuracy (predicted ÷ actual) |

| Relationship | Input | Output—derived from pipeline, but filtered and weighted |

Stage vs Forecast Category

It's also critical to distinguish between stage (a progression milestone like Discovery, Negotiation, Closed-Won) and forecast category (Commit, Upside, Pipeline). A deal can be in a late stage like Negotiation but still be categorized as 'At Risk' or 'Pipeline' if the close date is shaky or key stakeholders haven't engaged. Effective forecasting requires managing the intersection of both dimensions—not treating stage progression as automatic confidence.

Erosion refers to the systematic loss of expected value as opportunities move through stages and new information arrives. It manifests in several ways: deals marked as 70% likely that were never better than 30%, opportunities that slip repeatedly and eventually die, and zombie deals that linger in 'open' status long after the buyer has moved on. The common thread is a gap between recorded probability and reality.

Consider a deal that enters the 'Negotiation' stage with an 80% probability assigned by the rep. The stage label suggests it's nearly closed, but the underlying facts tell a different story: the economic buyer hasn't been engaged, procurement hasn't reviewed the contract, and the last substantive communication was three weeks ago. Historically, deals with this engagement pattern close at roughly 35%. That 45-point gap between recorded and actual probability is erosion waiting to happen.

Compression is the downward pressure on realized deal size and margin that occurs late in the sales cycle. It happens when competitive dynamics heat up, when procurement scrutinizes pricing, and when internal pressure to 'get something in' before quarter-end pushes reps to accept discounts they wouldn't have taken earlier. A deal that started at $400K and closes at $280K has compressed by 30%—but most forecasting systems treat that original $400K as the expected value right up until the moment of truth.

Compression is particularly insidious because it's often invisible until close. The deal is 'won,' so it doesn't feel like a failure. But across a portfolio, consistent 15-25% compression represents millions of dollars of expected revenue that never materializes.

Stalls and slippage are the temporal expressions of these phenomena. Academic research on opportunity conversion consistently shows that time-in-stage and periods of inactivity are among the strongest predictors of eventual loss. When a deal stays too long at a given stage without observable progress, or when it's repeatedly pushed to a future close date, its true conversion probability declines sharply—even if it remains marked as 'late-stage' in the CRM.

The pattern is familiar to any experienced seller: a deal that was 'closing this month' for three consecutive months is almost certainly not closing at all. Yet these deals often remain in the forecast, their stale optimism polluting the signal with noise.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

Before exploring why erosion happens, it's worth quantifying the stakes. Organizations with uncalibrated pipelines typically experience 20-40% erosion from initial commit to final close. For a company targeting $10 million per quarter, that represents $2-4 million of expected revenue that evaporates—every quarter.

The downstream effects compound. When forecasts are unreliable, finance builds in larger buffers, which constrains investment. Sales leadership loses credibility with the board. Hiring and capacity planning become guesswork. Marketing can't accurately attribute pipeline to campaigns. And perhaps most damaging, the organization develops a culture of accepting forecast misses as inevitable, which erodes accountability and masks underperformance.

The alternative—a well-calibrated forecast where an 80% commit closes roughly eight times out of ten—transforms how a business operates. Leaders can make confident decisions about investment, capacity, and strategy. The revenue engine becomes predictable. Variance becomes something to manage rather than something to survive.

The Diagnosis - Why Erosion Is Predictable

The insight that should be both troubling and encouraging is this: erosion follows patterns. Research on business analytics for software sales pipelines demonstrates that the relationship between nominal stage and true win probability is often weak without disciplined governance. In many organizations, opportunities advance stages based on subjective judgment or optimistic interpretation of buyer signals. The result is a pipeline that is consistently overstated relative to historical conversion rates.

From a mathematical perspective, a forecast is an expected value calculation across a portfolio of uncertain events. If you have ten deals, each with a 70% win probability and $100K value, the expected value of that portfolio is $700K. But here's what matters: the actual outcome will almost never be exactly $700K. It will be $600K or $800K or $500K, depending on which specific deals close. That variance around the expected value is not noise—it's signal.

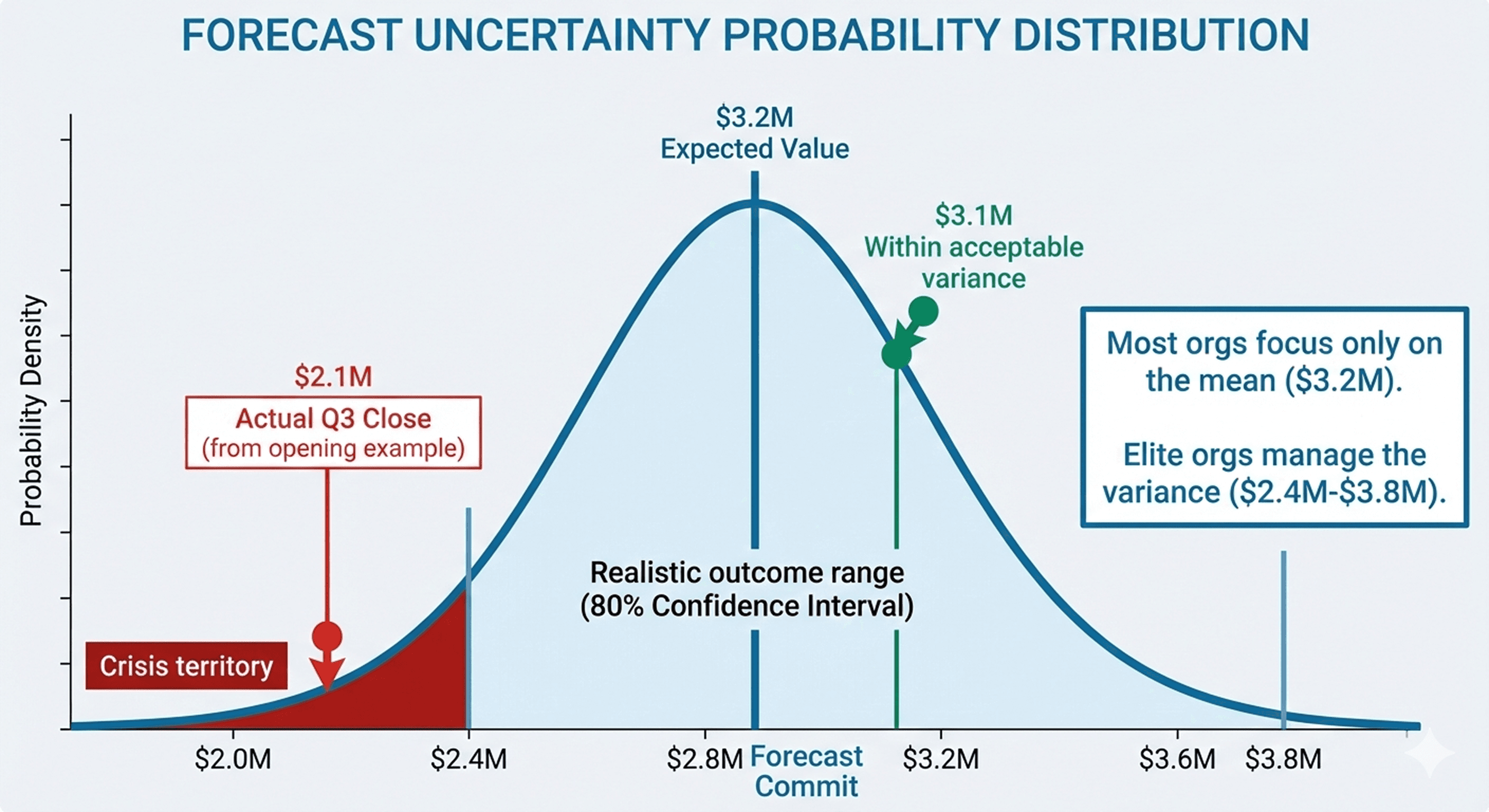

In forecasting, we care deeply about two properties: the mean (are we centered on the right number?) and the variance (how wide is the range of likely outcomes?). Most organizations obsess over the mean while ignoring variance entirely. They forecast $3.2 million and celebrate when they hit $3.1 million, without acknowledging that the true uncertainty band was $2.4 million to $3.8 million. When you ignore variance, you can't properly staff, you can't set realistic expectations with the board, and you can't distinguish between good execution and good luck.

A critical distinction: Expected value is powerful for long-term capacity planning and understanding portfolio health across multiple quarters. But for quarterly execution and the 'commit' forecast, expected value can be misleading. You cannot close 47% of a deal. In the current quarter, deals are binary—they either close or they don't. A commit forecast built purely on probabilistic weighting might show $3 million in expected value, but if you only have four deals that are genuinely above 80% confidence, and they total $2.2 million, then $2.2 million is your real ceiling. Use expected value for planning the portfolio; use high-confidence binary thinking for calling the quarter.

The other mathematical reality: deal outcomes are not independent. When one enterprise deal stalls because procurement is overwhelmed, it's a signal that other deals facing procurement may also stall. When the macro environment tightens, compression doesn't hit randomly—it clusters. Most forecasting models assume independence, which systematically underestimates the probability of correlated failures.

The mathematical challenge would be manageable if humans were good at estimating probabilities. We're not. Decades of research on judgment and decision-making reveal systematic biases that distort forecasts in predictable ways.

Optimism bias is the tendency to overestimate positive outcomes and underestimate risks. In sales, this manifests as reps who genuinely believe a deal is 80% likely when the data suggests 40%. They're not lying—they're miscalibrated. The champion seemed enthusiastic, the demo went well, and the buyer said 'this looks great.' Those signals feel like certainty, but they're not. Research on industrial sales lead conversion shows that subjective confidence is a weak predictor of actual close rates without external calibration.

Anchoring compounds the problem. Once a rep assigns a value or probability to a deal, that number becomes an anchor that resists adjustment even as new information arrives. A deal that started at $500K stays at $500K in the CRM even after scope discussions suggest $300K is more realistic. A 70% probability persists even after the champion loses budget authority. The initial anchor creates inertia, and small downward adjustments feel like concessions rather than corrections.

Confirmation bias ensures that we notice evidence that supports our existing forecast and discount evidence that contradicts it. When a deal is in your commit, you interpret silence as 'they're busy working through internal approvals' rather than 'they've deprioritized this.' You remember the enthusiastic email from last month and forget the two unreturned calls this week.

The sunk cost fallacy keeps dead deals alive. After spending three months on an opportunity, engaging multiple stakeholders, and building custom demos, it becomes psychologically difficult to admit the deal is lost. So it lingers in late-stage, marked as 'negotiation,' even though the buyer has clearly moved on. The organization has invested time and resources, and closing the opportunity feels like admitting waste.

Sandbagging: The opposite distortion. While much of this article focuses on over-optimism, seasoned sales reps also distort forecasts in the opposite direction—they sandbag. Sandbagging occurs when reps intentionally underreport deal probability, hold back deals from the forecast, or delay stage progression to create a cushion. Why? To hedge against missing their number, to ensure they can be the hero when deals 'suddenly' close, or to game incentive structures that reward beating the forecast.

Sandbagging is just as damaging to forecast accuracy as over-optimism. It creates artificial 'bluebird' deals that close unexpectedly, which ruins the organization's ability to learn what actually predicts success. When deals consistently appear from nowhere in the final week, managers can't distinguish between genuine late-stage acceleration and hidden pipeline. More critically, machine learning models and calibration algorithms depend on honest data—if reps are systematically underreporting, the training data is poisoned and the model never learns the true conversion patterns.

The solution is not to eliminate rep judgment—it's to calibrate it. Organizations that track forecast accuracy by rep, provide feedback loops, and create psychological safety for honest assessment see meaningful improvement. The key insight from research on superforecasting is that accuracy improves when forecasters receive regular feedback on their predictions and when the culture rewards calibration over optimism.

Even well-calibrated individuals produce bad forecasts if the system is broken. In many organizations, the incentive structure actively punishes honest assessment.

Reps are often compensated on closed deals but judged on pipeline generation and forecast commitment. The result is predictable: inflate the pipeline to show activity, sandbag the commit to ensure you beat it, and hope that some subset of inflated pipeline randomly converts. When missing a forecast triggers scrutiny but beating it triggers celebration, reps optimize for the path of least resistance—conservative commits and optimistic pipeline.

Stage definitions are another structural failure point. In theory, stages represent observable milestones in the buyer journey. In practice, they're often subjective, poorly defined, and gamed. If moving a deal to 'Negotiation' requires only that a proposal was sent, rather than that the economic buyer has reviewed it and legal is engaged, then 'Negotiation' becomes meaningless. Deals pile up in late stages because the label is easy to achieve, even when the underlying progress is absent.

The lack of exit criteria exacerbates this. Many CRMs define what's required to enter a stage but not what's required to stay there. A deal can sit in 'Proposal' for six months without triggering any flag, even though time-in-stage is one of the strongest predictors of loss. Without automatic signals that a deal has stalled, the pipeline becomes a junk drawer of aging opportunities that no one wants to close because it would hurt their metrics.

Finally, there's the problem of forecast category discipline. Many organizations treat 'Commit' as a negotiation rather than a prediction. Reps know they need to show a certain commit number, so they include deals that are really 60% likely, hoping some combination will get them there. The forecast category becomes detached from probability, which defeats the entire purpose.

All of the above would matter less if sales organizations had pristine data. They don't. CRM data quality is notoriously poor, and poor data produces poor forecasts.

The most common data quality issues are missing fields, stale information, and inconsistent definitions. When 40% of deals lack a next step, last activity date, or primary contact, any attempt at algorithmic forecasting collapses. You can't predict what you can't measure. Stale data—opportunities with close dates six months in the past still marked 'open,' contacts who left the company but remain the primary relationship—pollutes the training set for any predictive model.

Inconsistent definitions across regions, segments, or teams are equally damaging. If 'Discovery' means something different in the enterprise team than it does in the commercial team, you can't build a unified model. If one manager lets reps mark deals as 'Verbal Commit' based on a casual conversation while another requires documented executive sign-off, the category is meaningless.

Lead source matters more than most realize. Not all pipeline is created equal. Inbound SMB deals generated by content marketing behave very differently from outbound enterprise deals sourced by SDRs. The win rate, sales cycle, average deal size, and compression patterns vary significantly by source. Yet most organizations apply universal stage probabilities and conversion assumptions across all sources, which systematically over- or under-states different segments.

For accurate forecasting, you need to segment pipeline by lead source and build separate conversion models for each segment. An inbound Product-Qualified Lead converting at 25% in a 30-day cycle is fundamentally different from an outbound enterprise opportunity converting at 8% over 180 days. Blending them together produces a useless average that fits nothing.

The hidden cost of bad data is that it prevents learning. Even if you implemented perfect governance and eliminated bias tomorrow, you couldn't build a reliable model because your historical data doesn't reflect reality. You'd need six months of clean data before any algorithmic approach would work. This is why data discipline isn't optional—it's the foundation of everything else.

The Prescription — Building Systems That See

If erosion is predictable, measurable, and patterned, then the solution is not to work harder or hope for better luck. The solution is to build systems that surface the signals early and operating models that respond to them. This requires three things: governance that creates reliable data, algorithms that extract signal from that data, and inspection cadences that translate signal into action.

The foundation of any reliable forecast is stage governance. Stages should represent observable, verifiable buyer actions—not seller activities or wishful thinking.

Discovery should require documented pain, budget authority identified, and a clear decision process outlined. Not just 'we had a good conversation.' Evaluation should require active engagement from multiple stakeholders, a defined evaluation timeline, and comparison against alternatives. Negotiation should require an economic buyer engaged, legal or procurement review initiated, and a specific close date agreed upon. And critically, each stage should have exit criteria: if a deal has been in 'Evaluation' for 90 days with no stakeholder activity in the last 30 days, it should automatically flag for review or move back to an earlier stage.

The goal is not bureaucracy—it's signal clarity. When a deal reaches 'Negotiation' under these conditions, that label actually means something. You can assign a meaningful probability based on historical conversion from that stage, because the stage represents a real state of buyer readiness.

This also means ruthlessly pruning dead deals. Many organizations resist closing opportunities because it lowers pipeline coverage, but a bloated pipeline full of zombie deals is worse than a lean pipeline of real opportunities. The right metric is not 'total pipeline' but 'qualified pipeline'—opportunities that meet the minimum standards for their stage and have shown recent activity.

One of the most critical—and most commonly confused—operating rhythms is the distinction between pipeline reviews and deal reviews. They serve different purposes and require different structures, but many managers conflate them, which is why erosion happens.

Pipeline Review (Data Hygiene): This is a scrubbing exercise focused on forecast accuracy and data quality. The goal is to remove stale opportunities, validate stage assignments, and ensure the forecast categories (Commit, Upside, Pipeline) reflect reality. This should happen weekly and be highly structured. Questions include: Has there been activity in the last 14 days? Does the close date make sense? Are the stage exit criteria actually met? Is the forecast category appropriate given the engagement pattern?

Pipeline reviews are about ruthless honesty. If a deal is in 'Negotiation' but the economic buyer hasn't engaged, it gets moved back or flagged. If a deal has slipped three times, it gets downgraded or closed. The output is a clean forecast that leadership can actually trust.

Deal Review (Strategy Coaching): This is a coaching session focused on how to advance specific opportunities. The goal is to help reps think through deal strategy, identify risks, and plan next steps. This should happen biweekly or monthly and be much more exploratory. Questions include: Who is the economic buyer and have we engaged them? What's the competitive landscape? What objections are likely to surface? What's our plan to get to verbal commit?

Deal reviews are about improving win rates and velocity on important opportunities. They're collaborative, strategic, and forward-looking. The output is better-informed reps and higher-quality deals in the pipeline.

The critical distinction: Pipeline reviews are about the forecast; deal reviews are about the deals. When managers try to do both in the same meeting, they end up doing neither well. Reps hide problems to avoid the scrutiny of a hygiene review, which means the coaching never happens. And the forecast stays polluted because the focus shifted to strategy instead of scrubbing.

Elite revenue organizations separate these two cadences explicitly, with clear expectations about what each is for. Pipeline reviews are non-negotiable, data-focused, and brief. Deal reviews are optional (focused on key deals), strategy-focused, and in-depth. Both matter, but they cannot be combined.

Humans are bad at probabilistic thinking, even with training. The most effective organizations augment human judgment with algorithmic support. This doesn't mean replacing reps—it means calibrating them.

The goal of algorithmic forecasting is to produce a probabilistic model that ingests observable data—stage, time-in-stage, engagement patterns, past activity, stakeholder involvement, competitor presence—and outputs a calibrated win probability. This probability isn't a replacement for rep judgment; it's a benchmark against which rep judgment can be compared and adjusted.

The Build vs. Buy Decision: The article's earlier framing may have suggested that RevOps teams should build custom machine learning models from scratch using tools like XGBoost or random forests. While these techniques are technically sound, that advice is dangerous for 95% of organizations. Building and maintaining a production-grade forecasting model requires significant data science expertise, clean historical data at scale, and ongoing model maintenance. Most companies lack the volume of data, the technical talent, or the infrastructure to do this well.

For most organizations, the right answer is to buy a Revenue Intelligence platform like Clari, Gong, BoostUp, or Aviso. These platforms have pre-built models trained on millions of deals across hundreds of companies. They ingest data from your CRM and communication tools, apply sophisticated algorithms, and provide calibrated forecasts out of the box. They also provide the inspection tools, dashboards, and workflows that make the output actionable.

If you do choose to build: The essential inputs to any forecasting model are stage, time-in-stage, days since last activity, stakeholder engagement level (number of contacts, seniority of contacts, activity types), changes in deal size, changes in close date, and historical conversion rates segmented by deal characteristics (source, segment, competitor). Models like gradient boosting decision trees (XGBoost) or ensemble methods work well because they can handle non-linear relationships and interactions between variables. The model should output a probability (0-100%) for each deal, along with a confidence interval, and should be retrained quarterly as new close data becomes available.

Whether you build or buy, the key is to use the algorithmic output correctly. The model's probability isn't gospel—it's a signal. When a rep says a deal is 80% likely but the model says 40%, that's not a fight about who's right. It's a conversation starter. What does the rep see that the model doesn't? What patterns is the model detecting that the rep is discounting? The goal is calibrated synthesis—using the algorithm to surface discrepancies and improve human judgment over time.

Lagging indicators tell you what happened after it's too late to fix. Leading indicators tell you what's about to happen while intervention is still possible. The most effective revenue organizations build leading indicator systems that surface erosion risk before it materializes in missed forecasts.

Key leading indicators for pipeline health include weighted pipeline coverage by stage (not just total coverage), percentage of pipeline in late stages with next steps defined, average time-in-stage by stage (flagging outliers), percentage of commit deals with activity in the last 7 days, slippage rate (deals that have pushed close dates), compression rate (deals that have reduced in value), staleness (deals with no activity in 14+ days), and forecast accuracy by rep over the trailing two quarters.

These indicators should be surfaced in a weekly dashboard reviewed by leadership. The purpose is not to shame reps but to identify patterns. If 30% of commit deals have no activity in the last week, that's a signal that the commit is overstated. If average time-in-stage for 'Evaluation' is growing, that's a signal that deals are stalling. If slippage rate is increasing, that's a signal that timing assumptions are breaking down.

The value of leading indicators is that they create urgency before the crisis. When you can see erosion building in week six, you can intervene—pull forward early-stage deals, increase manager involvement on key opportunities, or reset expectations with leadership. When you only see it in week twelve, your options are limited.

Not all pipeline is the same, and treating it as uniform produces systematically biased forecasts. Effective forecasting requires segmentation along the dimensions that actually drive variance.

By deal size: Enterprise deals behave differently from mid-market, which behave differently from SMB. Enterprise deals have longer cycles, more stakeholders, higher win rates conditional on reaching late stages, and more compression. SMB deals have shorter cycles, fewer stakeholders, lower late-stage win rates (because the qualification bar is lower), and less compression. Applying the same stage probabilities across these segments is a mistake.

By lead source: Inbound marketing-qualified leads convert differently than outbound SDR-sourced leads, which convert differently than partner referrals. Each source has its own qualification bar, buyer intent signal, and engagement pattern. Segmenting by source allows you to build conversion models that reflect these differences rather than washing them out with averages.

By sales rep: Some reps consistently underforecast, others consistently overforecast. By tracking forecast accuracy at the rep level, you can apply a calibration factor—if a rep has historically overstated commit by 20%, you can adjust their current forecast accordingly. This isn't about penalizing optimism; it's about extracting the useful signal from each rep's judgment while correcting for their systematic biases.

By competitor presence: Deals with specific competitors present often have different win rates, cycle times, and compression patterns than uncontested deals. If you know that deals against Competitor X historically compress by 25%, you can factor that into your expected value for current deals where they're present.

The goal of segmentation is to move from a single universal forecast to a portfolio of segment-specific forecasts. The aggregate is more accurate because each segment is modeled on its own terms rather than being distorted by the average.

Behavior follows incentives. If your compensation plan rewards pipeline generation without penalizing poor qualification, you'll get bloated pipelines. If your culture celebrates beating forecasts but punishes missing them, you'll get sandbagged commits. If stage progression improves rep metrics but there are no consequences for stale deals, you'll get inflated stages.

Effective organizations align incentives with the behaviors they want. This means compensating reps not just on closed deals but on forecast accuracy over time. A rep who consistently submits accurate forecasts—both commits and misses—should be recognized, because they're providing the organization with reliable signal. A rep who beats forecast by 50% every quarter is either an exceptional closer or is systematically underreporting, and both possibilities need investigation.

It also means creating psychological safety for bad news. If a rep is penalized for downgrading a deal from commit to upside, even when it's the right call, they'll wait until the last minute to admit it. But if the culture rewards early honesty—'you called this accurately in week six, which gave us time to respond'—then reps will surface problems early.

Incentive alignment also applies to managers. If a manager's performance is judged purely on whether their team hits the number, they'll pressure reps to overcommit. But if they're also judged on forecast accuracy and the quality of their pipeline governance, they'll balance growth with realism.

Improving forecasting isn't just about systems and algorithms—it's about improving the humans in the system. Research on superforecasting consistently shows that people can improve their probabilistic judgment through training, feedback, and deliberate practice.

Effective training programs start with bias awareness—teaching reps and managers about the cognitive traps that distort forecasts. Sessions on optimism bias, anchoring, confirmation bias, and the sunk cost fallacy make these concepts concrete and relatable. The goal is not to eliminate bias (you can't) but to recognize when you're falling into a trap and correct for it.

Training should also include calibration exercises. Give reps a series of historical deals and ask them to estimate win probabilities. Then show them the actual outcomes and the aggregate accuracy. Over time, with feedback, people's calibration improves. They learn that 'the demo went well' doesn't mean 80%—it means 45%. They learn that 'we've been working this for three months' is not a reason to stay optimistic—it's a reason to reassess.

Finally, training should normalize uncertainty and encourage range-based thinking. Instead of asking 'what's the probability this closes,' ask 'what's the range of likely outcomes?' Instead of committing to a single number, provide a confidence interval. This shift in framing reduces overconfidence and forces more honest assessment.

The Therapy — Tactical Plays That Reduce Erosion

Systems and governance create the foundation, but execution happens in the deals. The following tactical plays are organized by the specific erosion problem they address. Each play is derived from analysis of what differentiates winning deals from losing or stalling deals.

Compression happens when deals shrink late in the cycle due to competitive pressure, procurement scrutiny, or internal desperation to close. The following plays specifically address compression risk:

Anchor high and justify rigor. Compression often starts with an initial price that lacks credibility or justification. Instead of leading with a discount-ready price, anchor high with a clear rationale tied to business outcomes. When procurement pushes back, you negotiate from a strong position rather than immediately caving. Deals that start with clear ROI documentation compress 40% less than deals that rely on relationship or feature lists.

Engage procurement early. Many reps avoid procurement until forced to, which means they only appear when a deal is at risk. Instead, bring them into the process during evaluation. Frame your offering in terms they care about—total cost of ownership, risk mitigation, implementation support—and address their concerns before they become objections. Deals where procurement is engaged before the proposal stage compress half as much as deals where they arrive at negotiation.

Create urgency that isn't quarter-end. The worst compression happens when the only urgency is your fiscal calendar. Buyers know you're desperate and will wait you out. Instead, create urgency tied to their outcomes—regulatory deadlines, product launches, competitive pressures. When the urgency is theirs, not yours, compression drops significantly.

Walk away from bad deals. The deals that compress the most are the ones you should have qualified out earlier. A buyer who's only interested if you discount 40% is not a good customer. A deal that's been negotiating on price for six weeks with no progress is not going to close cleanly. Having the discipline to walk away from compressing deals forces buyers to reengage on your terms or self-selects for better customers.

Slippage happens when close dates push repeatedly, which is usually a signal of weak urgency, incomplete stakeholder alignment, or unclear next steps. The following plays specifically address slippage risk:

Mutual close plans. Slippage is often caused by asymmetric expectations—the rep thinks the deal is closing Tuesday, the buyer thinks they're still evaluating. A mutual close plan is a shared document that lists every step remaining (legal review, security review, procurement approval, executive sign-off), who owns each step, and the timeline. When both sides agree to it, accountability increases and slippage decreases by 60%.

Champion validation. Many deals slip because the person you're working with isn't the actual decision-maker or doesn't have the influence you think they do. Validate your champion by asking them to arrange meetings with the economic buyer, getting them to confirm the decision process, and observing whether stakeholders actually respond to their requests. If your champion can't make those things happen, they're not really a champion, and the deal will slip.

Test close dates. Don't accept a close date at face value. Ask 'what has to happen between now and then?' If the buyer lists ten things and none of them have started, the close date is fictional. If they can't articulate the steps, the close date is fictional. Real close dates come with real plans. Testing reveals whether the date is real or aspirational, which lets you re-forecast accurately rather than being surprised by slippage.

Red-flag repeated pushes. The first time a deal slips, it might be legitimate. The second time, it's a pattern. The third time, the deal is almost certainly not closing. Build a discipline where any deal that slips twice gets moved out of commit or closed entirely unless there's a documented change in circumstances (new executive, new budget, new initiative). This prevents stale deals from polluting your forecast.

Many deals erode because they were never real to begin with. Weak qualification at the top of the funnel cascades through every stage. The following plays improve qualification so that only real opportunities enter the pipeline:

MEDDIC or equivalent framework. MEDDIC (Metrics, Economic Buyer, Decision Criteria, Decision Process, Identify Pain, Champion) or similar qualification frameworks force reps to gather specific information before advancing deals. The key is enforcement—if a deal doesn't have documented answers to these questions, it doesn't advance. Deals that pass strict MEDDIC qualification convert at 3-4x the rate of deals that don't.

Pain validation, not feature matching. Weak qualification focuses on whether the product fits. Strong qualification focuses on whether the pain is urgent and expensive. If the prospect's current state is tolerable, they won't buy—even if your product is superior. Validate that the pain is costing them money, time, or competitive position, and that fixing it is a priority this quarter. If it's not, the deal isn't real yet.

Budget confirmation. 'We'll find budget if the ROI is there' is not budget confirmation. Real budget confirmation means they've identified the budget line, confirmed the amount, and know the approval process. If they haven't done this, they're not serious. Don't spend cycles building a business case for someone who hasn't confirmed they can actually buy.

Disqualify early. The best reps are as good at disqualifying as they are at closing. If a prospect doesn't meet the qualification criteria, close the deal as 'lost' and move on. This keeps your pipeline clean, lets you focus on real opportunities, and paradoxically often causes the prospect to reengage when they realize you're not desperate. Weak reps let every conversation linger; strong reps ruthlessly disqualify.

Stalled deals are opportunities that have stopped progressing—no stakeholder activity, no next steps, no response to outreach. The following plays are designed to either restart momentum or force a final disposition:

Executive outreach. When a deal stalls at the rep level, escalate to executive outreach. Have your VP or CRO reach out to their counterpart. The message is not 'why haven't you responded to my rep' but rather 'I wanted to personally ensure we're aligned on the value and timeline.' Executive involvement often breaks through organizational inertia and forces a response—even if the response is 'we're not moving forward.' Either way, you get clarity.

Requalify from scratch. Stalled deals often stall because the original qualification was weak or circumstances changed. Treat the stall as a reset—go back to basics and requalify. Has the pain changed? Is the champion still in role? Is budget still available? Has the decision process shifted? If you can't reconfirm these basics, the deal is dead. If you can, you've found the path to restart.

Offer a break. Counter-intuitively, one of the best ways to restart a stalled deal is to offer to stop pushing. Send a message like: 'It seems like the timing isn't right. I'm going to take you out of our active pipeline, but I'll check back in six months. If something changes before then, let me know.' This often triggers a response because it removes pressure and creates a loss-aversion response. If it doesn't trigger a response, you've confirmed the deal is dead and can close it cleanly.

Time-box the stall. If a deal has had no activity for 30 days, it gets flagged. At 45 days, it moves to a 'stalled' category with a specific reactivation plan. At 60 days with no progress, it gets closed. This discipline prevents zombie deals from clogging the pipeline. It also creates urgency—reps know they have 30 days to restart momentum or lose the opportunity from their number.

Win/loss analysis by competitor reveals which competitors you win against, which you lose to, and what differentiates winning deals in competitive situations. Use this data to build competitor-specific battle cards—not just feature comparisons, but winning messaging, positioning, and documented responses to their common tactics.

Create early warning indicators for competitive deals. If certain competitors consistently appear in late stages and create compression, flag deals when they're mentioned in notes or emails. Define response protocols triggered by specific competitor mentions—if Competitor X appears, engage a technical expert; if Competitor Y appears, schedule executive engagement immediately.

Document winning messaging from deals where you successfully displaced specific competitors. What did you say? What proof points resonated? What objections did you overcome? Turn these into replicable plays rather than one-off hero moments.

Analysis of lost and stalled deals reveals the most common objections and which objections are most likely to kill deals at each stage. Prioritize objection handling training based on frequency and impact—don't waste time on objections that rarely occur or rarely matter.

Create stage-specific objection playbooks. Early-stage objections ('we're not ready to buy') differ from late-stage objections ('your price is too high'). The responses should also differ. Trying to handle a budget objection in discovery is premature; trying to handle a pain objection in negotiation is too late.

Document successful reframes and responses from deals that overcame specific objections. When a rep successfully navigates 'we need to see ROI before committing budget,' capture what they said and said and how they structured the conversation. Turn individual success into organizational knowledge.

Build pre-emptive strategies that address likely concerns before they're raised. If you know that 'implementation complexity' is a common objection in enterprise deals, address it proactively in your evaluation presentation rather than waiting for them to bring it up. Objections handled proactively close 2x as often as objections handled reactively.

Rep-level variance analysis shows where individual reps diverge from team benchmarks—in conversion rates, forecasting accuracy, deal velocity, and compression. Use this data to create coaching frameworks tied to specific, measurable gaps.

Build one-on-one templates that focus on the metrics most predictive of success for that rep. If a rep converts discovery to evaluation at 60% but the team average is 80%, the coaching should focus specifically on discovery qualification and stakeholder engagement—not generic 'improve your pipeline.'

Develop deal review checklists based on characteristics of won deals. What questions should a manager ask to surface whether a deal is real? What patterns should they look for? What red flags should trigger deeper investigation? These checklists ensure consistent coaching quality across managers.

Establish skill development paths based on where each rep underperforms relative to benchmarks. If a rep's issue is qualification, the path includes MEDDIC training, shadowing top qualifiers, and joint calls with a manager. If the issue is closing, the path includes negotiation training, objection handling drills, and executive engagement practice. Coaching becomes data-driven rather than intuition-driven.

The deeper insight is that a data-informed playbook isn't a static document—it's a system that updates as you learn. Every quarter, as new conversion data comes in, the playbook should evolve. Stage definitions tighten based on what's actually predictive. Qualification criteria update based on which segments are converting. Engagement standards recalibrate based on patterns from recent wins. Competitive plays refresh based on recent win/loss analysis.

Most playbooks are written once and gather dust. A playbook built on this analytical foundation has a built-in refresh mechanism: the data tells you when and where to update. When you see that deals with a specific engagement pattern are converting at higher rates, you codify that pattern as a new best practice. When you see that a particular objection is killing more deals than it used to, you build a new response. The playbook becomes a living artifact of organizational learning.

Conclusion: From Surprise to Signal

Pipeline erosion, compression, and stalls will never be eliminated entirely. Complex B2B sales involve genuine uncertainty, competitive dynamics, and human behavior that cannot be perfectly predicted. But most of what organizations experience as 'bad luck' is actually measurable, patterned, and improvable.

The path forward requires treating the pipeline as a probabilistic portfolio rather than a deterministic list. It means tightening stage governance, aligning incentives with forecast accuracy, and investing in bias awareness across the team. It means building leading indicator systems that surface problems while intervention is still possible. It means implementing algorithmic forecasting—whether built or bought—to calibrate human judgment. And it means developing a culture where early bad news is rewarded rather than punished.

Most importantly, it requires distinguishing between the two core forecasting methodologies: expected value for long-term planning and high-confidence binary thinking for quarterly execution. Use probabilistic weighting to understand portfolio health, capacity needs, and multi-quarter trends. But when it comes time to call the quarter, focus on the deals that are genuinely above 80% confidence—because those are the only ones you can actually count on.

When these elements come together, erosion stops being a mysterious quarter-end shock and becomes a manageable, monitorable, and improvable property of the revenue engine. That transformation—from surprise to signal—is the core competency that separates organizations that merely survive their forecasts from organizations that actually run their business on them.

The question for every CRO and RevOps leader is simple: Which kind of organization do you want to be?

Further Reading

For readers who want to go deeper, these six sources are the most valuable starting points:

On forecasting bias and how to fix it: "Sales Teams Aren't Great at Forecasting. Here's How to Fix That" (Harvard Business Review, 2019). The most accessible overview of why sales forecasts systematically miss and what organizational changes help.

On superforecasting principles: "Superforecasting: How to Upgrade Your Company's Judgment" by Tetlock and Schoemaker (Harvard Business Review, 2016). The foundational work on calibration, probabilistic thinking, and managing forecasters rather than just forecasts.

On decision-making traps: "Outsmart Your Own Biases" (Harvard Business Review, 2015) and "The Hidden Traps in Decision Making" (Harvard Business Review, 1998). Essential reading on the cognitive biases that distort pipeline decisions—anchoring, sunk cost, confirmation bias, and overconfidence.

On CRM and pipeline analytics: "CRM and Sales Pipeline Management: Empirical Results for Managing Opportunities" by Peterson and Rodriguez. Academic research showing the relationship between stage governance, data quality, and forecast accuracy in B2B sales.

On lead conversion modeling: "Industrial Sales Lead Conversion Modeling" by Monat. Demonstrates how behavioral and timing variables predict conversion better than stage labels alone.

On forecasting under uncertainty: "3 Ways to Improve Sales Forecasts When the Future Is Unclear" (Harvard Business Review, 2020). Practical guidance on scenario-based planning and updating assumptions in volatile environments.

References

Harvard Business Review Sources

"Sales Teams Aren't Great at Forecasting. Here's How to Fix That." Harvard Business Review, March 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/03/sales-teams-arent-great-at-forecasting-heres-how-to-fix-that

"3 Ways to Improve Sales Forecasts When the Future Is Unclear." Harvard Business Review, September 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/09/3-ways-to-improve-sales-forecasts-when-the-future-is-unclear

Tetlock, Philip E. and Schoemaker, Paul J.H. "Superforecasting: How to Upgrade Your Company's Judgment." Harvard Business Review, May 2016.

"Outsmart Your Own Biases." Harvard Business Review, May 2015. https://hbr.org/2015/05/outsmart-your-own-biases

Hammond, John S., Keeney, Ralph L., and Raiffa, Howard. "The Hidden Traps in Decision Making." Harvard Business Review, 1998.

"How to Choose the Right Forecasting Technique." Harvard Business Review, July 1971. https://hbr.org/1971/07/how-to-choose-the-right-forecasting-technique

Academic Sources

Peterson, Robert M. and Rodriguez, Michael. "CRM and Sales Pipeline Management: Empirical Results for Managing Opportunities." Campbell University.

Monat, Jamie. "Industrial Sales Lead Conversion Modeling." Available via Semantic Scholar.

TU Darmstadt. "Business Analytics for Software Sales Pipelines." Technical University of Darmstadt.

Moore, Don A. and Bazerman, Max H. "Decision Making and Judgment in Management." Harvard Business School, 2022.

Various authors. "Leading Indicators in Economic and Sales Forecasting." PMC/National Institutes of Health; Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 2025.